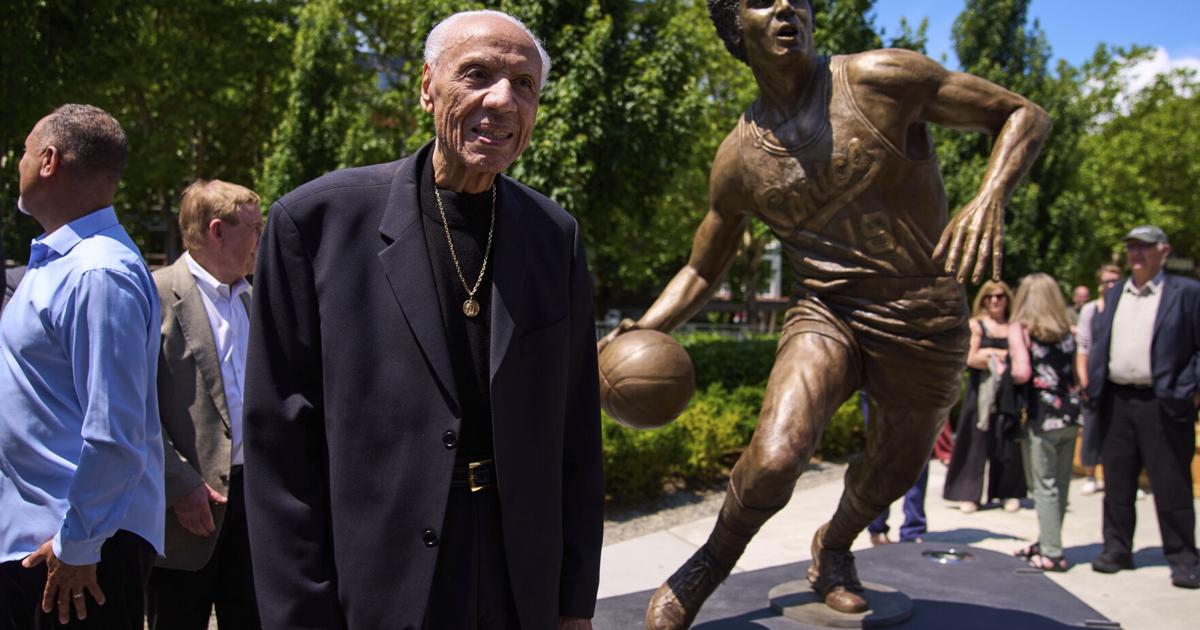

Lenny Wilkens, a perennial all-star NBA point guard who became one of the winningest coaches in league history and was among the few Hall of Famers inducted as both a player and coach, died Nov. 9. He was 88. His family confirmed the death to the Associated Press. Information on where and how he died was not immediately available. At 6-foot-1 and 180 pounds, Mr. Wilkens was comparatively diminutive among the players he competed against for 15 seasons during the 1960s and 1970s with the St. Louis Hawks, Seattle SuperSonics, Cleveland Cavaliers and Portland Trail Blazers. But he was smooth and deceptively quick, a lefty who had honed his game on the outdoor courts of Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. He was unafraid to glide through a crowd for a layup or dish a no-look pass to a teammate. He also played dogged defense. Quiet, cerebral and unselfish, Mr. Wilkens was an unmistakable floor general along with other titans of the era, including Oscar Robertson, Jerry West and Walt Frazier. “He’s probably the smartest backcourt man we ever face,” Bill Bradley, a star forward for the New York Knicks, told Sport magazine in 1973. “The only guy who might compare to him is Jerry West, but I think Lenny is a little more conscious of mismatches and open men than West.” A 1994 Sports Illustrated profile by Gary Smith described Mr. Wilkens’s phenomenally quick hands on defense and eyes that saw everything on the court. But there was something more to him, an intense but unemotional will that he channeled into his game. “He has made it his life’s business not to let feelings migrate to his muscles, to his nerves,” Smith wrote. “One minute left. One-point game. Give him the ball.” Defenders knew Mr. Wilkens favored going to his left with the ball, but few could stop him. After the 1967-68 season, in which he averaged 20 points and 8.3 assists per game for the Hawks, he finished second in the MVP balloting to Wilt Chamberlain, the 7-foot-1 Philadelphia 76ers star. Mr. Wilkens was named to nine all-star teams and to the NBA’s 50th and 75th anniversary teams. In eight seasons with the Hawks, he consistently led his team to the playoffs but never to a championship. In 1969, with Seattle, he became the NBA’s second Black head coach, after the Boston Celtics’ Bill Russell. Like Russell, he began as a player-coach, scoring 38 points and adding 12 assists in his first coaching victory. As a coach, he followed the same dispassionate approach he had cultivated as a player and became known for turning moribund teams into winners. His bland demeanor disguised a fierce, driven competitiveness. “I tell guys from the beginning that this is the way it is here, and I define their roles,” he told USA Today in 1994. “I don’t treat anyone special. Everybody knows the parameters, and I don’t make allowances for anyone, because it’ll come back and bite you later on.” He modeled his coaching style after that of Red Auerbach, the coach who shaped the Celtics dynasty of the 1950s and 1960s and whose 938 wins were the most of any NBA coach before Mr. Wilkens surpassed him in 1995. “I think I’ve been able to read talent and maximize what each guy has,” he told the Oregonian in 1994, noting Auerbach’s similar ability to do that. “A lot of people didn’t like Red, or were irritated because he was always beating them, but he maximized his talent, okay?” After serving as player-coach for the SuperSonics and the Trail Blazers, Mr. Wilkens retired as a player in 1975. He returned to Seattle in 1977 as director of player personnel but, 22 games into that season, the team was floundering with a 5-17 record, and Mr. Wilkens took over as head coach. He led a remarkable turnaround, guiding the Sonics to a 42-18 record in 60 games and on to the NBA Finals, where they lost to the Washington Bullets in a hard-fought seven-game series. The next season, his Seattle team – led by Gus Williams, Dennis Johnson and Jack Sikma – beat the Bullets for the franchise’s only title. Despite his remarkable two-season record with the Sonics, Mr. Wilkens was passed over for the NBA’s Coach of the Year both times. His only Coach of the Year award came after 1993-94 season, when he led the once-mediocre Atlanta Hawks to a 57-25 record. As coach of the Cleveland Cavaliers in the 1980s and early 1990s, Mr. Wilkens won more than 50 games four times in six seasons. But his team had the misfortune of being in the same division as the Chicago Bulls, with the league’s dominant star, Michael Jordan, who eliminated the Cavs in the playoffs four times. Mr. Wilkens held the top job at six franchises over a 32-year career and was the first NBA coach to reach 1,000 victories. His final coaching stop was with his hometown New York Knicks. When he retired in 2005, with a record of 1,332-1,155, he had the most wins – and most losses – of any NBA coach in history. Gregg Popovich and Don Nelson later passed him on the all-time wins list, but Mr. Wilkens was on the sideline for nearly 2,500 regular season games, still the record for NBA coaches. Longtime NBA coach Doc Rivers bristled at how Mr. Wilkens was often overlooked in discussions of the league’s great coaches. “Look at Lenny’s record,” Rivers told Andscape, an ESPN website, in 2020. “He coached in Seattle, they won a world championship. He goes to Cleveland, Cleveland had struggled for years, they win immediately. He goes to Atlanta, Atlanta starts winning. It’s to me, the Black code: ‘He’s a player’s coach. He’s a motivator.’ No, Lenny was a coach. Lenny ran great stuff. Lenny was great out of timeouts. Lenny was a hell of an X and O coach.” A difficult childhood Leonard Randolph Wilkens Jr. was born in Brooklyn on Oct. 28, 1937. He was the oldest of four children of a Black chauffeur and a candy-factory worker of Irish descent. He was 4 when his father died of a perforated ulcer. The family lived in a cold-water apartment with four children sharing a single room. While still in elementary school, Mr. Wilkens began delivering groceries to help his mother make ends meet. Because he was biracial, he suffered taunts and looks of disdain throughout his youth and was called “half-breed” by other children. “If I let that hurt me, who has the anxiety?” he told Sports Illustrated in 1994. “Me. I was not going to let anyone hurt me or make me feel anxious. I’d learned something by then. If I could control myself, I could make them feel anxious.” Father Thomas Mannion, a priest at the local Catholic church, became a father figure and mentor. Baseball was Mr. Wilkens’s favored sport in Dodgers-crazy Brooklyn, and he idolized Jackie Robinson, who broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947. But Mr. Wilkens gravitated to basketball, and his skills emerged while playing in Catholic Youth Organization leagues and at Brooklyn’s Boys High School. Mannion persuaded Joe Mullaney, the coach at Providence College in Rhode Island, to give Mr. Wilkens a scholarship and a chance to show off his hoops skills. “Lenny was a self-made man by the time he was 10,” Mannion said to Newsday in 1994. “He had responsibilities, so he had an awareness of who he was. He had an uncanny capacity to lead.” At Providence, at the time a Catholic men’s college, Mr. Wilkens was one of just six Black students among 1,200 White men. He became a two-time all-American and, in his senior year, he was named MVP of the National Invitation Tournament. Mr. Wilkens was considering a career in teaching when he watched the 1960 NBA Finals between the Celtics and St. Louis Hawks and realized he could hold his own in professional basketball. Soon after graduating with a bachelor’s degree in economics in 1960, he was selected by the Hawks in the first round of the NBA draft, after Robertson and West, who would be his longtime rivals on the court. Mr. Wilkens spent a large swath of his second season in the Army. When he returned to the Hawks, he made the all-star team while focusing on passing the ball to Hawks’ stars Bob Pettit and Cliff Hagan. Off the court, Mr. Wilkens faced racial discrimination in St. Louis. Neighbors poisoned his dog, and he was greeted with stony silence when he entered an all-White restaurant – where he was pictured in a Hawks team photo. Mr. Wilkens married his childhood sweetheart, Marilyn Reed, in 1962. They had two daughters, Leesha and Jamee, and a son, Leonard Randolph Jr. In addition to his wife and children, survivors include seven grandchildren. After finishing second to Chamberlain in the MVP voting in 1968, Mr. Wilkens demanded a salary increase. The Hawks instead traded him to Seattle, a struggling expansion team, where he averaged a career-high 22.4 points per game in his first season. A year later, he became the player-coach. In addition to coaching in the NBA, Mr. Wilkens led the 1996 U.S. Olympic basketball team to a gold medal. He was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame as a player in 1989 and as a coach in 1998. “What I’d like people to remember is that anyplace I went, I made a difference in that our teams became competitive,” Mr. Wilkens told Andscape in 2020. “They could compete. They knew how to win. And every time they stepped on the floor, they represented true professionalism. Places I went, we won.”

https://www.phillytrib.com/obituaries/lenny-wilkens-nba-hall-of-fame-player-and-coach-dies-at-88/article_7e890763-2d8c-45fd-8963-7c30889353c6.html

Lenny Wilkens, NBA Hall of Fame player and coach, dies at 88